Shocking figures for gender diversity on the management boards of German banks

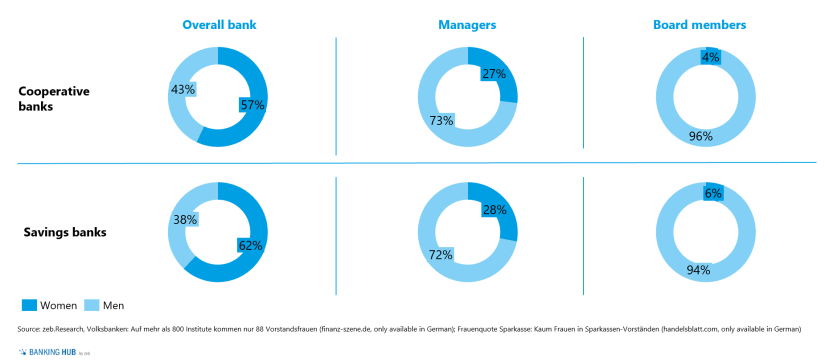

German banks have been facing a huge challenge for years. This time, it’s not about external issues such as the low interest rate phase or changing customer behavior, but about a problem that has arisen internally: the proportion of women in top management positions is extremely small. At Germany’s 100 largest banks, women account for just about 10% of board members[1].

The figures for savings banks and cooperative banks are even more alarming: the share of women on the management board at savings banks is 6.1% and at cooperative banks it is as low as 4.5%[2]. At cooperative banks, the number of board members named Thomas (93) is higher than the total number of female board members (88)[3].

If the number of female board members of the 100 largest German banks continues to grow at the current rate, gender balance will not be achieved until 2098[4]. Unfortunately, based on the figures of the last few years, we cannot even assume a linear development. For this reason, it will probably take even longer. If we apply the low annual growth rate of around 1% of the last two years, gender parity at cooperative banks will only be achieved in 281 years.

Over the last few years, the savings banks have not been able to exceed a growth rate of 3%. In fact, a negative trend can currently be observed with the number of female board members actually declining[5]. Although society, economy and politics are increasingly giving attention to diversity issues, the topic is progressing at a snail’s pace.

Gender diversity as a catalyst for sustainable business success

The sheer injustice of this disparity alone makes the situation problematic. However, there is also a scientifically proven interrelation between the proportion of women in top management positions and business success. For example, for every 10 percent increase in gender diversity among executives, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) rise by 3.5 percent[6].

Scientific studies show that gender-diverse teams are more creative, more productive and therefore more successful[7]. A higher percentage of women in management positions also boosts innovation in companies[8].

In order to ensure long-term business success, sustainability and ESG (environmental, social and governance) topics are currently high on the agenda of many management boards (zeb offer for ESG integration).

Among many other topics, diversity is an aspect of the letter “S” in ESG, as gender equality is enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDG 5 of “gender equality” is about, among other things, getting more women into leadership positions in business, politics and academia[9].

It is not without good reason that the topic of diversity can also be found, for example, in the sustainability map of cooperative banks. It becomes a tangible field of action at the latest when sustainability is implemented consistently and systematically.

In addition, banks can no longer afford gender disparity considering the insufficient number of young professionals and hence the shortage of specialists and managers. “Banker” has no longer been at the top of the list of the most popular professions of job starters for several years now. In light of this fact, it is no surprise that banks are in a battle for talent. Many board members are now also worried about their own reputation, since the issue of gender diversity is gaining increasing attention and visibility in the media.

Reasons for this disparity – the problem seems to be of our own making

How is it possible that there are so few women in executive positions when, at least at savings and cooperative banks, two-thirds of the workforce is female? Evidently, there is a sufficient number of women who could be trained as managers – just like men.

The reason that is most frequently given to explain why the quota of women in management positions is so low: there are too few women with appropriate professional qualifications. However, studies demonstrate that women are no less qualified than their male colleagues[10].

And what does appropriate professional qualification mean anyway? Do managers today still need to know every single step of their employees’ work process? Or does the manager rather act as an initiator who creates a setting which allows employees to work efficiently? The self-image of bank managers plays a major role in personnel selection.

Another reason that is very frequently given is: women care more about their families than their professional careers. This traditional model of family which continues to stick in people’s minds is outdated. Women are more likely to opt for family life when a bank fails to offer them attractive career prospects. For example, too few banks offer flexible working models. Consequently, career paths are often designed for men who work full-time while women have to face career setbacks related to family planning.

In addition, more than half of the participants in surveys said that fewer women want to take on leadership roles than men do[11]. Statements that go in a similar direction include: “women don’t assert themselves – they need to act with more determination” or “no woman applied for the management position”. Such assertions are often motivated by the encouragement of traditionally male behavior in banks and a corporate culture in which employees move ahead with a dog-eat-dog attitude.

Women are no less ambitious than men. When women do not apply for advertised positions, they frequently feel that the wording of the job ad does not address them or that the position is unattractive to them for other reasons.

Der perpetual “Thomas cycle”…

The decisive reason, however, why progress is sluggish, as outlined above, is never mentioned in surveys, because it is ingrained in each of us (including women!) as an unconscious bias which stems from the principle of self-similarity. We prefer to surround ourselves with people whose attitudes and patterns of behavior are similar to our own. This leads to men predominantly recruiting men who are very similar to them in origin, education and age – resulting in the perpetual “Thomas cycle”. Women almost always hit a glass ceiling and are less likely to be promoted on the basis of their skills and potential[12].

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

The way out of the perpetual “Thomas cycle”

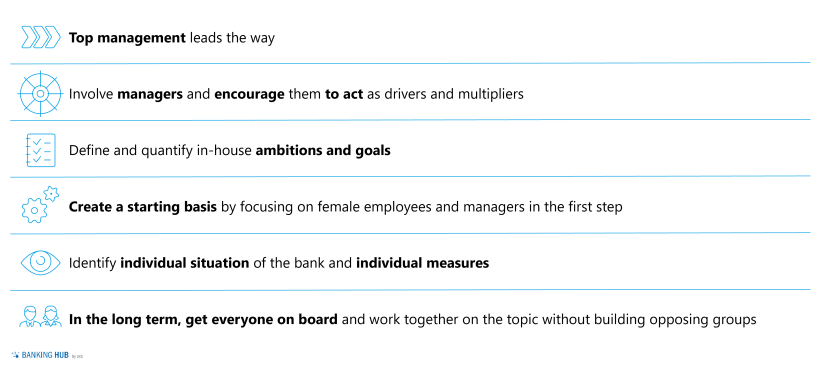

So what can banks do to end the perpetual “Thomas cycle”? The very first step is to acknowledge that there is a lack of diversity in the bank and that this is a problem.

Male board members and executives tend to underestimate the extent of gender bias in their institution because they are not affected by it personally. Therefore, addressing the topic, raising awareness among executives and questioning one’s own behavior are important first steps.

HR processes often need to be adapted too; first and foremost the staffing process. To work against the principle of self-similarity, recruitment teams need to have more diverse members who have been made aware of cultural criteria for assessment and promotion.

Transparent and completely objective criteria should be established for evaluating competency, which are then applied to the hiring and promotion process. This also includes such simple things as advertising all positions and not resorting to unofficial ways to fill them.

In addition, dealing with mothers as leaders is an essential element. The prevailing public image of childless women in management positions has been outdated for a long time. A study of the resumes of female board members found that 91 percent are married and 70 percent have at least one child[13].

Banks should therefore reconsider how they deal with employees on parental leave and those returning from parental leave. How are employees updated about what’s going on at the bank during parental leave? What options are there for re-entry, also in terms of flexible working models or part-time management positions?

These are just a few of a whole range of measures banks can adopt to promote gender diversity.

Success factors for more gender diversity

Studies now reveal where the difference lies between pioneers and other banks. The greatest success factor is to make the issue of gender equality a strategic priority[14]. When management boards tackle this issue, they have to become strong advocates for equal opportunity in their bank and bring this mindset to their team.

Giving this topic great strategic importance also means setting specific, quantifiable targets, as is done with all other strategically relevant areas in the bank. In the earnings forecast, there are target figures for earnings and costs, in process controlling for processing times, and in the target agreement for employees, for example, there are targets for construction financing volumes. The proportion of women in management positions can only be increased if a “gender target” is defined for each management level – or in other words, a quota.

Banks that have set a women’s quota work more consistently on equal opportunity and as a result are more successful in increasing the proportion of women. These banks are convinced that they profit from equality between female and male executives and that it contributes to greater business success.

If banks want to maintain their competitive position, there is no way around gender equality. Now it is essential to analyze the bank’s status quo, identify individual measures and create a starting basis for more gender diversity.

Diversity has many facets. Do you, too?

Lay an important cornerstone for equal opportunities at your bank right now!