State of the banking industry

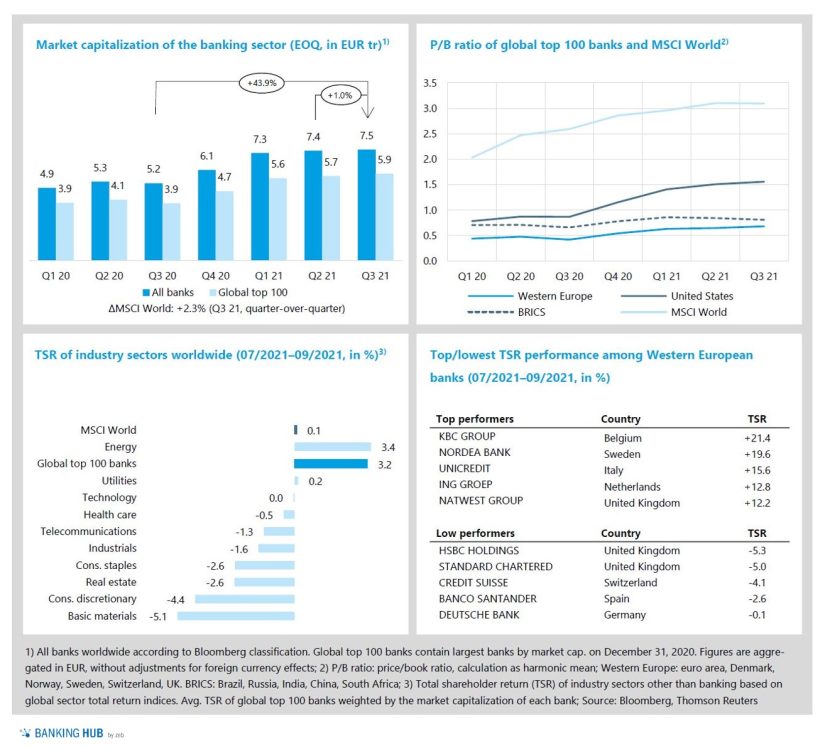

- Global capital markets have lost some momentum in Q3 2021 due to rising inflation and a struggling Chinese property developer – TSR of MSCI World was just +0.1% QoQ.

- The global top 100 banks, however, showed a strong Q3 performance with a TSR of +3.2% QoQ – mainly driven by Western European banks (TSR +6.2% QoQ) and U.S. banks (TSR +4.1% QoQ).

Global capital markets have lost some momentum in Q3 2021. Worries over rising inflation, the reaction of central banks as well as the impact of the struggling Chinese property developer Evergrande have interrupted the positive trend in Q3 2021 (MSCI World TSR +0.1% QoQ, market capitalization +2.3% QoQ).

The global top 100 banks, however, showed a strong Q3 performance, mainly driven by Western European and U.S. banks. Market capitalization of the global top 100 increased by +2.9% QoQ and TSR by +3.2% QoQ, the second largest TSR of all industries.

- In Q3, global top 100 banks’ market capitalization reached a new high of EUR 5.9 tr. The market cap of the overall global banking industry improved slightly by +1.0% to EUR 7.5 tr, almost reaching the pre-pandemic value 0f EUR 7.6 tr in Q4 2019.

- Global top 100 banks’ share price development showed clear regional differences in Q3. Western European banks showed the strongest average TSR of +6.2% QoQ, followed by S. banks with +4.1% QoQ. However, Asia-focused and especially Chinese banks suffered from growing uncertainty about the Chinese markets, therefore BRICS banks’ TSR decreased by -0.6% QoQ.

- Average P/B ratios also reflect these developments. In Q3, U.S. and Western European banks’ valuations continued their positive trend (U.S.: 1.56x; Western Europe: 0.68x) while BRICS banks’ P/B ratio declined to 0.81x (-0.03x QoQ).

- HSBC and Standard Chartered are among the European low performers as both banks’ significant exposure to the Chinese market caused increasing concerns among the investors. By contrast, KBC showed a quarterly TSR of +21.4% based on strong interim results and substantial rate hikes of the Czech Central Bank, raising the earnings forecasts of KBC’s significant Czech business in the upcoming quarters.

Economic environment and key banking drivers

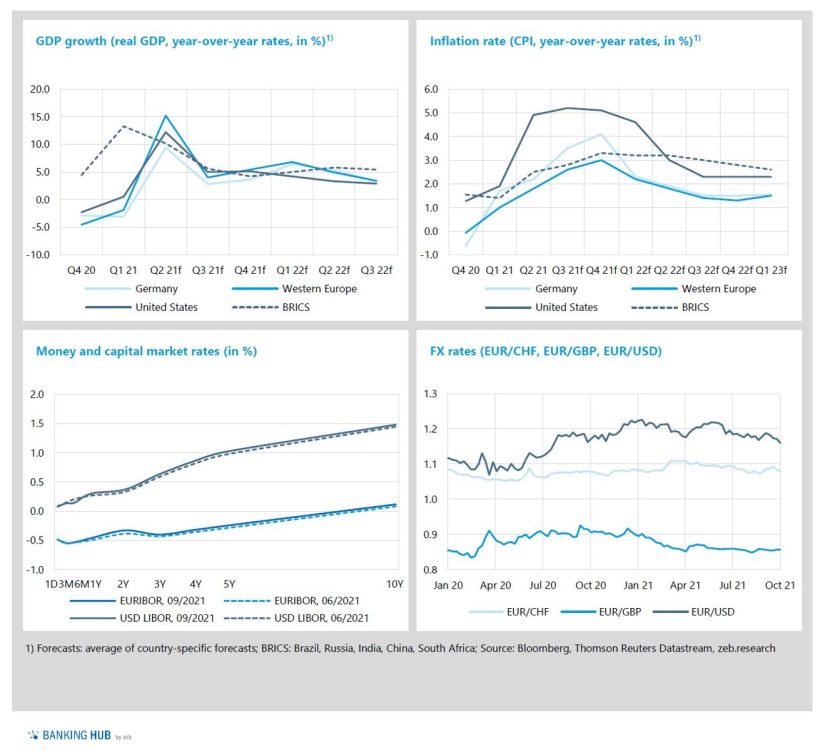

- Although new COVID-19 surges and strained supply chains are still challenges for the economic recovery, GDP growth is expected to remain strong in major regions in the upcoming months.

- Inflation risks are becoming more evident as supply bottlenecks appear to be larger and longer-lasting than expected, keeping inflation at a high level.

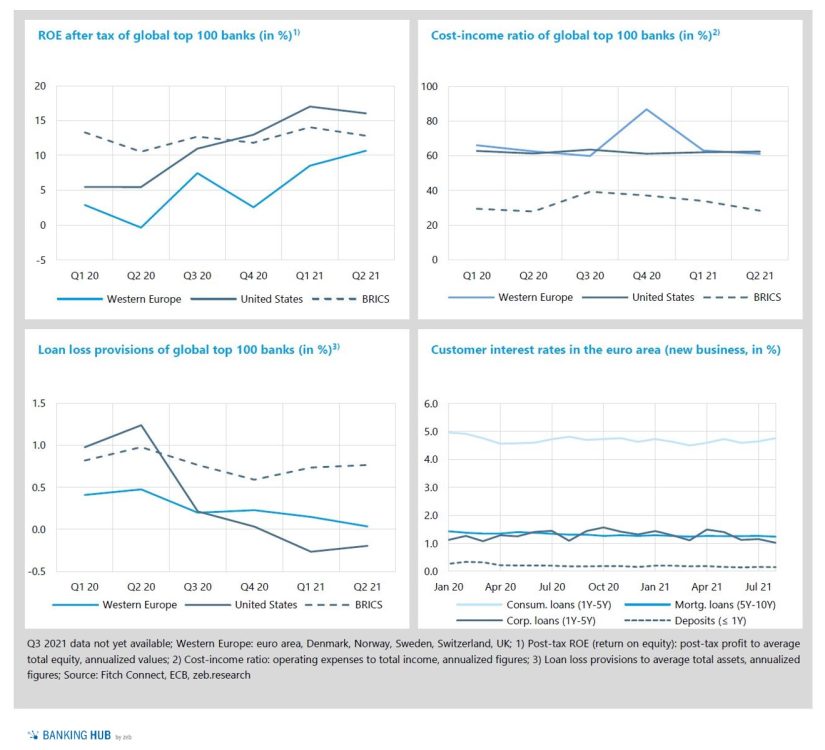

- Second quarter results of the largest global banks have been mostly good news – especially Western European banks showed strong results and the average ROE improved by +2.2%p QoQ to 10.7%.

As countries around the world are further reopening their economies, overall economic growth is about to reach pre-pandemic levels. Although new COVID-19 surges and strained supply chains still pose challenges for the global economic recovery, GDP growth is expected to remain strong in major regions in the upcoming months.

Supply bottlenecks, however, appear to be larger and longer-lasting than expected, keeping inflation at a high level until at least the end of the year. As inflation risks become more evident, the pressure on central banks to withdraw from their loose monetary policy is rising.

- GDP growth is expected to slow down in the third quarter across all major regions. After double-digit rates in the previous quarter, GDP growth is expected to reach +4.0% YoY in Western Europe and +5.0% YoY in the U.S. but will likely remain around these levels for the next quarters.

- Inflationary pressure is building up noticeably but varies across regions. Especially in the U.S., inflation rates rose sharply in Q2 and are expected to peak in Q3 with a value of +5.2% YoY. By the end of 2022, U.S. inflation rates will settle down to 2.3%. Western European inflation will reach its highest level of +3.0% in Q4 2021 but is expected to moderate below 2% by Q2 2022.

- U.S. Fed and ECB are still reacting calmly to inflation but both central banks have adjusted/softened their long-term targets in order to allow inflation to run temporarily higher than 2%. As a result, the euro area and USD yield curve remained nearly unchanged, just shifting slightly upwards compared to the previous quarter.

- The euro continued its downward trend against the US dollar and fell below 1.16, the lowest value for 14 months, as the U.S. Fed is heading for a first moderate tightening of its loose monetary course.

Second quarter results of the largest global banks have been mostly good news and several large U.S. and European banks were, again, able to beat consensus estimates. A dynamic capital market business along with an improving economic outlook and thus significantly lower reserves for credit losses boosted banks’ profitability.

Especially Western European banks showed strong results, with profitability (ROE) improving on average by +2.2%p QoQ to 10.7%. Third quarter results are likely to continue the positive trend, although less strongly.

- In Q2 2021, average profitability of U.S. and BRICS banks decreased slightly (U.S.: -1.0%p, BRICS: -1.2%p) but U.S. banks’ ROE remained strong at 16.0%, far above pre-pandemic levels. Western European banks continued their positive trend and profits increased by +24% QoQ, thus pushing the average ROE into the double digits.

- Western European banks were able to further improve their operational efficiency and the average cost-income ratio reduced to 61.1% (-2.0%p QoQ, -1.5%p YoY). Compared to previous year’s figures, Western European banks’ revenue grew by +7.3% YoY, also supported by positive effects from ECB’s TLTRO-III program (see our previous issue for details), in line with a higher cost base of just +4.8% YoY.

- As the economic situation brightened, banks continued to reduce LLPs they built up during the pandemic. In Q3, U.S. banks seemed to be more optimistic as LLPs stayed into the negative at -0.20% (+0.06%p QoQ). Western European banks further reduced risk provisions by -0.11%p QoQ (-144%p YoY) while LLPs decreased to 0.04% on average, still implying some caution.

- Euro area loan rates also reflect the improved economic situation. While rates for corporate loans decreased due to a lower loan demand as well as better credit quality, consumer loan rates increased in line with higher consumer spending.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

Special topic

Money, money, money? – Central banks’ own answer to the crypto boom

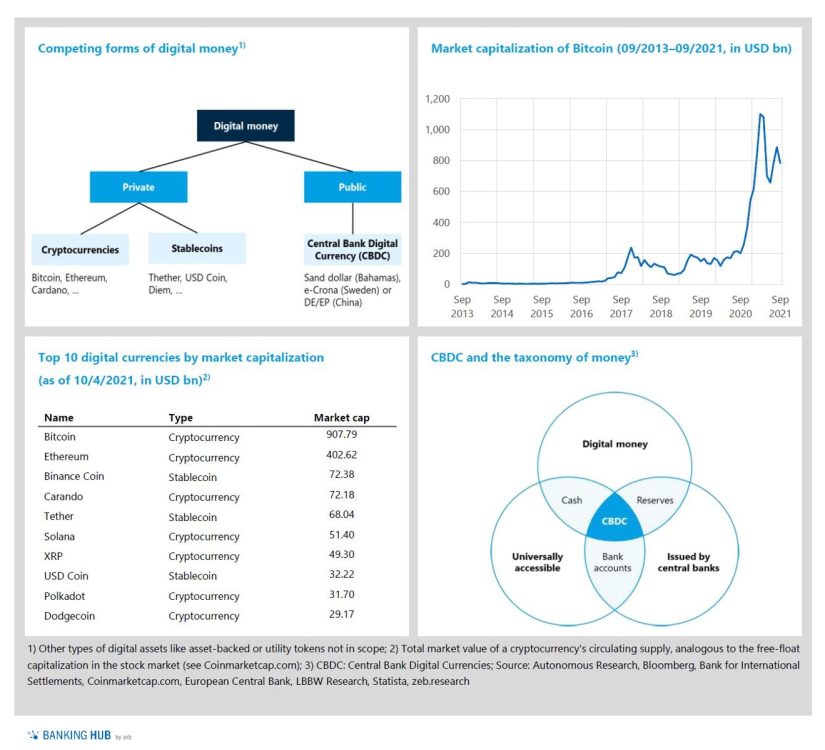

- Digitalization of money is taking off – private cryptocurrencies and other digital assets have experienced a real boom and are becoming more and more relevant in the financial and monetary system.

- Central banks are entering the competition by developing their own, “official” digital currency, i.e. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC).

- The direct impact on banks may be small for the time being but it is just the beginning of a new world of digital money.

Digitalization of money is taking off. Private cryptocurrencies and other digital assets have experienced a real boom and are becoming more and more relevant in the financial services sector. Several central banks around the world have already responded to this evolution by developing their own, “official” digital currency and the ECB started its project in July 2020. How can we explain central banks’ increased interest and what are the effects of a central bank digital currency on the banking sector?

Digital money is not new and has existed for decades, e.g. in the form of bank deposits or reserves of commercial banks. However, the digital revolution has led to the evolution of a variety of private alternatives, i.e. cryptocurrencies and stablecoins. Both are fully decentralized and can be used without the need for intermediaries (banks).

Cryptocurrencies have no relation to public money and no intrinsic value – the well-known Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency, introduced in 2009. Stablecoins are also digital currencies but pegged to an existing fiat currency, a basket of currencies, a cryptocurrency or commodities and therefore less volatile. Popular examples are Tether or Facebook’s planned Diem.

Since the introduction of the Bitcoin, more and more of such digital money alternatives have come to market, now reaching a total of around 12.800. Especially since the beginning of 2021, currencies have experienced a real boom and market capitalization has multiplied. For example, Bitcoin jumped up by +350% between the end of September 2020 and the beginning of October 2021 to around USD 900 bn – the total crypto market is estimated to be around USD 2.2 tr.

Looking at the top 10 digital currencies, Bitcoin and Ethereum are by far the largest players, covering nearly 60% of the whole market. Like the huge number of different cryptos, their properties and use also differ strongly. For instance, Bitcoin is designed as alternative money and its value is only derived from its shortage as it is clearly limited by code. Therefore, Bitcoin has rather been used as a (speculative) investment asset, like gold, also leading to extreme price volatility.

Ethereum is a decentralized and open source blockchain whith smart contract functionalities and thus provides more useful economic applications. Although not all forms of private digital money will remain in the market, there is enough room to coexist – as a pure payment solution or even beyond.[1] Now central banks are entering the competition by developing their own digital currency – but why now?

Generally, cash usage is changing and has declined in most developed markets. For instance, in European countries like Germany or Spain, cash usage decreased by -17%p (Germany) or -25%p (Spain) between 2010 and 2019. Even in countries where cash usage is already very low, this value shrank further – e.g. in Sweden the usage declined by -9%p to just 13% between 2010 and 2019. This development indicates a growing popularity of digital payment solutions, a trend that benefits any form of private digital money.

Since June 2019, central banks’ attitude to digital currencies has changed significantly as one of the largest BigTech companies, Facebook, announced the launch of a stablecoin named Diem (previously called Libra, pegged to a basket of several currencies). The distinct advantage of this BigTech currency over central bank fiat money is that it can be used as both payment instrument and payment infrastructure without regional restrictions and the need for other intermediaries.

A broad and global acceptance of such private stablecoins or other kinds of digital money would pose a threat to the monetary authority of central banks and potentially the stability of the financial system. If private digital money became a parallel currency, central banks could lose control of their monetary system. If other financial services were based on such parallel currencies, with a lack of transparency and without a sound regulatory framework, the risks in the financial system would also increase significantly.

The COVID-19 pandemic may additionally act as a catalyst here. In times of exploding government debt and increasing inflation, people may lose confidence in the traditional fiat money system, which supports the acceptance of such private digital money and therefore the shift to parallel currencies. Consequently, some central banks are already working on their own Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC). In general, this kind of currency is still fiat money, issued by central banks but provided in digital form, and will extend physical cash and central bank reserves.

Unlike bank accounts (deposits), CBDCs are completely backed by central banks and therefore risk-free. Interestingly, the first country working on such an initative was the Bahamas, which rolled out its Sand Dollar in October 2020. Other central banks like the Swedish Riskbank (e-Crona) and the People’s Bank of China (DE/EP) are currently in the testing or pilot phase. Due to the growing currency competition and new “digital projects” by these central banks, the ECB decided to start its own project of a digital euro on July 14, 2021. However, what can the banking industry expect from these developments?

Depending on the concrete design, CBDCs could have an impact on the intermediary function of banks and therefore could weaken the banking sector. In a model where central banks directly issue CBDC, central banks will compete with commercial banks for deposits. Thus, a switch from deposits to CBDC can have the same impact as a withdrawal of cash from bank accounts. This kind of balance sheet reduction could ultimately lead to higher financing costs for banks and also support increased risk-taking.

Furthermore, a declining importance of bank deposits could reduce banks’ information on their customers and weaken banks’ risk assessment capability. Finally, CBDC could have an amplifying effect in case of bank runs because customers can very easily transfer their deposits into safe central bank money.[2]

According to the current state of consultation of the ECB project, the digital euro is likely to be implemented with the involvement of the banks in a hybrid model. That is, CBDC is issued by the ECB and represents a liability of the central bank, but the administration and access of customers is transferred to commercial banks.

The focus will also be on the application for retail clients as a “digital banknote” with cash features, i.e. no interest, anonymity. In such a context, the direct impact on banks will be small for the time being. The architecture of payment transactions is expected to change little, and banks will take over the operational business of the digital euro and manage the digital wallets of the private sector.

However, this is just the beginning of a new world of digital money. More complex solutions for the Industry 4.0 or the B2B sector are also conceivable in the form of a private digital euro. The concrete developments are still uncertain but the traditional financial sector will and should be part of this new, digital currency payments infrastructure.